N.B. - The article below was published in Forum (Vol. 4, No. 3, 28 March 2003, pp. 6-7), official publication of the University of the Philippines (UP). The full text is also available at URL http://www.up.edu.ph/forum/2003/Mar03/subanon.html

The Subanon of Barangay Saad

Danilo Ara�a Arao

Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism

College of Mass Communication, UP Diliman

It is every urban dweller's painful ordeal, every mountaineer's occasional adventure and every settler's daily toil.

To say that Barangay Saad, home to about 65 Subanon families in Mt. Paraya in Zamboanga del Sur, is a "remote rural area" is an understatement. After all, going there means walking for six hours from Barangay Dapiwak (another "nearby" Subanon community) on pointed rocks, crossing rivers and traversing natural slopes which are at times slippery especially when raining (which was the case when I went there!).

For a second, I thought about turning back, but there was a need for me to be there. I was part of the team that gave a training on participatory research to the Subanon residents.

The way to Barangay Saad is so challenging that BOTH my sandals and spare slippers were damaged within just the first one-and-a-half hours of travel, forcing me to walk on foot the rest of the way. This is no easy task given the trail of sticky mud, slippery rocks and strong currents while crossing rivers.

To prevent slipping or being carried by raging waters, I held on to tree branches or sturdy leaves and grass. The only consolation I found from the arduous travel is viewing nature at its most pristine state.

There is, of course, a sense of "victory" upon arriving in Saad. Then again, this feeling may not be so evident as my first instinct was to ask for drinking water and then throw myself in a makeshift bed cum dining table to rest my weary bones.

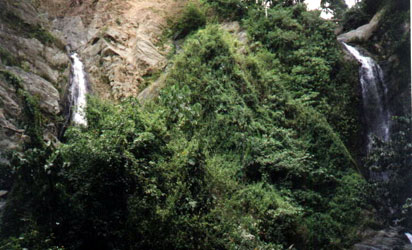

As I closed my eyes to take a short nap, my mind wanders back to the twin waterfalls on the way to Saad. It was truly a sight to behold as the rushing waters compete for the space on the ground, splashing against slippery boulders and imposing their presence by perpetually imitating the sound of rain.

The twin waterfalls of Barangay Saad, truly a sight to behold.

Then I began to snicker as I remembered the number of times I slipped, a feat only equalled by the number of times I had to assure my companions that I was okay. Some bruises and minor wounds on my legs and feet were proof of what I had to go through just to get to Saad.

A 30-minute shuteye did wonders for the body (and bruised ego), and there was an initial impression of paradise in a place that time forgot.

From our history subjects, we all know the Subanon tribe as one of the 13 indigenous peoples group in Mindanao called Lumad (born of the earth). They are also called Subanen, Subanu, and Subano.

The term is derived from the word "soba" or "suba" which means river and the suffix "nun" or "non" indicates place of origin. Subanon therefore means "a person or people of the river." They were initially from the lowland areas, but they were pushed to go to the mountains with the arrival of Spanish colonizers who claimed land ownership by virtue of a written land title.

Latest available data (1988) show that the Subanon population has grown to 300,000, most of them living along the Zamboanga peninsula.

Barangay Saad is home to a small percentage of the Subanon, as it is populated by a little more than 350 Subanon though the area spans 10,000 hectares.

The Subanon live a very simple life, a result not only of their cultural upbringing but also the deprivation of physical infrastructure that should provide basic services like communications, water and electricity.

Even if they live in an upland area where my temporary ordeal is just part of their daily routine, the Subanon people of Saad manage to make farmlands out of idle slopes, as well as get water from the nearby river for drinking and irrigation.

The limited influence of lowland culture may be gleaned from their manner of dressing. The Subanon men already wear shirts and pants, while the women don skirts or dusters. Their clothes, however, are predictably cheap and, at times, tattered. These are glaring manifestations of poverty in the area.

There is a basketball court in Saad, an indication that the Subanon have taken interest in the popular sport. Since there is no electricity, they only play in the morning when the heat of the sun is not as scorching as the late afternoon's.

(left) Children play in the basketball court of Barangay Saad very early in the morning.

(right) The Subanon of Barangay Saad wear ordinary clothing, part of the influence of lowland culture.

The Subanon hardly need to partake of cash to get what they need, though nature can prove to be an enemy during harvest seasons when production is low, which happens quite often.

The problem of low production, however, cannot just be blamed on the unpredictable changes in the weather, but also the lack of farm inputs. There are only four carabaos in the area, and most Subanon residents do not have plows and only use sundang (bladed weapon) and other simple tools for farming.

They cultivate the soil in groups in an age-old tradition called hunglos, where people tilling the land are divided into groups with three to 12 members each. They collectively help in cutting trees, as well as planting until harvesting of each member's land which normally spans one hectare. After working on one member's land, they then transfer to another member's, and so on until all the members' lands are attended to. Members of the group bring their own food, which they also willingly share to fellow members.

Of course, such ventures can only do so much given the inherent limitations of planting and harvesting in upland areas.

Mindful of the shortcomings in providing for the consumption needs of the Subanon living there, the Balay Danggawan No'k Subanen (BADASU, Welcome Home of the Subanen), a non-government organization, embarked on a research project in early 2000 to analyze the problem of low production and to identify socioeconomic projects that would help solve this problem. Consequently, BADASU helped in providing indigenous seeds and teaching the Subanon people appropriate and sustainable upland farm technology.

The farming skills and techniques, as well as the use of indigenous seeds (e.g., rice, corn, coconut) and organic inputs (e.g., compost) do not conflict with their age-old cultural beliefs. These even help in making life a bit more comfortable in the upland community, though the Subanon still recognize the need to assert their rights and to fight for government's recognition of their ancestral domain.

What is important to note at this point is that the Subanon way of life is not affected and they do not see upland farm technology as a capitalist venture that would ensure profit. In other words, the support given to them is just for their consumption needs that could more or less help in their struggle for change.

The Timuay spreads part of the chicken's blood on my palm.

The Subanon had been very appreciative of the help given to them. I was humbled by the recognition of being an "adopted son" by the Timuay (village elder and leader). The latter led a ceremony highlighted by the killing of a chicken and spreading part of its blood on my right palm. The Timuay did this while chanting a prayer in the Subanon language.

The blood on my palm has already been washed away but as an old adage goes, the memory of being there remains. I left the area with renewed strength and a fresh perspective of life. Notwithstanding the ordeal of going there, it was quite an uplifting experience and I would not mind returning in the near future.

Then again, I would have to bring more durable sandals next time around...